Steady Gains, Stubborn Gaps

Board Gender Diversity in 2023-2025

By Joanne G Salazar

Looking at the bigger, more widely traded listed companies, the numbers look a bit better: Morgan Stanley’s Capital Investment All Country World Index (MSCI ACWI) finds women hold 27.3% of board seats and 46.2% of companies have reached the “30%” critical-mass threshold, a target used by investors, indexes, and campaigns to signal meaningful representation beyond tokenism.

Welcome progress indeed, but most of that progress has been achieved in non-executive directorships. Female representation in top executive posts stalled or fell in 2024, underlining the persistent pipeline problem.

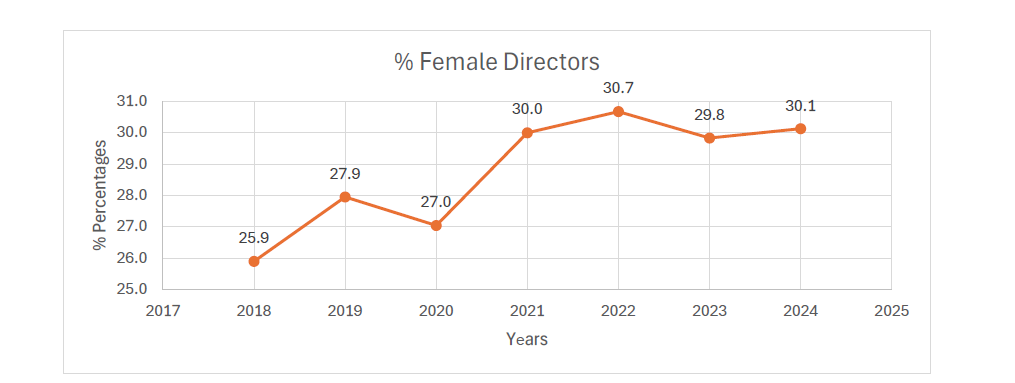

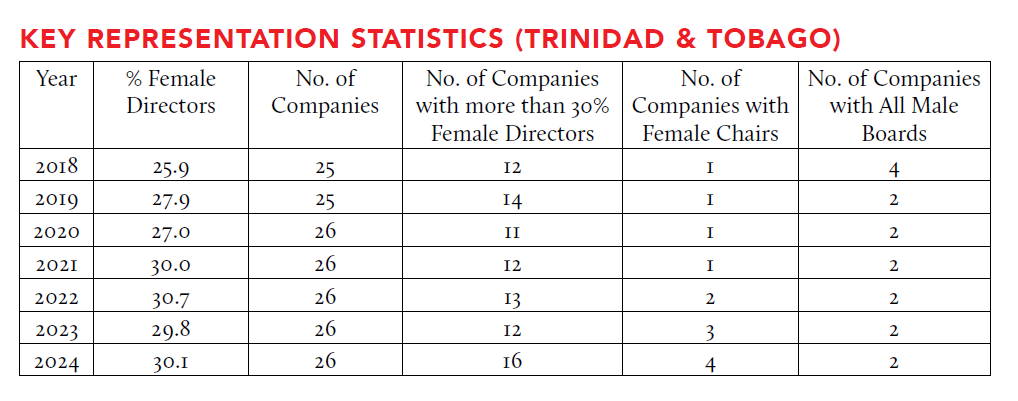

A regional case study: Trinidad & Tobago, 2018-2024

The seven-year dataset for companies listed on the Trinidad & Tobago Stock Exchange (TTSE) tells a clear story of gradual progress:

· The percentage female directors rose from 25.9% (2018) to 30.1% (2024)

· In 2024, there were 40 executive directors, 10 of whom (25%) were female

· Women as board chairs increased from 4.0% (2018) to 15.4% (2024)

· Women as CEOs were 20% (2024), however, note that because the pool of chairs and CEOs is small, single appointments can shift the percentages markedly year to year.

Figure 1- %Female Directors (2108-2024)

· In Trinidad and Tobago for 2024, 15 of 26 listed companies (58%) met or exceeded the 30% mark; 8 were at 40%+; 4 were at 50%+.

· Pipeline reality: As stated above executive seats are just 17% (40) of all board seats; women hold 25% (10) of those executive seats. By ‘pipeline’ we mean the flow of women into the feeder roles boards draw from—especially finance (CFO), operations (COO, BU heads) and technology (CIO/CTO). If women aren’t moving into and through these roles, board percentages can rise while power positions (Chair, CEO, committee chairs) remain stubbornly male.

Table 1 – Key Representation Statistics (Trinidad & Tobago)

What moved the needle

1) Binding rules accelerated change in Europe-and beyond

‘Binding rules,’ mean legal or listing-rule requirements, like the EU’s 2026 targets and Hong Kong’s ban on all-male boards, that force near-term action; these measures have driven faster gains than voluntary codes alone in many markets.

2) Voluntary, target-driven models can work-but need constant pressure

The UK’s business-led FTSE Women Leaders Review reports 43% women on FTSE 350 boards and 35% in senior leadership, showing that transparent public targets, annual league tables and investor scrutiny can deliver strong board numbers-even without quotas. But the UK itself warns leadership targets may be missed, and female CEO numbers remain thin.

The business-led, voluntary approach adopted in the UK and Australia have both moved the needle significantly and can be replicated locally. Although the pipeline reality mentioned above is a stubborn problem for both the legal and voluntary approached to addressing gender inequality on boards.

The power gap: where progress stalls

The power gap: where progress stallsAcross the G20, the averages tell the tale: 23% of board seats, 8% of chairs, 5% of CEOs and 12% of CFOs are women, underscoring gains at the table, but stubborn gaps in the most powerful positions. For boards serious about sustainable progress, the target has to widen from headcount to succession pathways into revenue-impacting roles, finance, and the board leadership track.

The Trinidad & Tobago data echoes that reality: board percentages rose 4.2 points in seven years, while the share of women chairs only inflected meaningfully in 2024. That suggests policy, investor attention or visible milestones (e.g., first female chair appointments) can catalyse rapid catch-up-once the slate is ready.

Quotas vs. voluntary initiatives

Whether jurisdictions adopt quotas or voluntary ‘comply-or-explain’ systems turns on constitutional risk, political appetite, investor pressure, regulatory capacity, and the depth of the executive pipeline. Where legal authority is clear and urgency is high, hard floors (e.g., a minimum share of women or a ban on single-gender boards) move numbers fastest. Where legal or political constraints are tighter, standardized targets with mandatory numeric disclosure and ‘comply-or-explain’ narratives can still deliver progress—especially when coupled with board-refreshment tools and pipeline metrics.

For many markets-including Caribbean exchanges-the UK model is politically and practically easier to adopt (targets, public scorecards, investor pressure) while strengthening listing-rule disclosures (e.g., board diversity policies, refreshment, and nomination-committee independence) to keep pressure on the system.

Talking points for Trinidad & Tobago 2024

1) Tokenism is fading; but power is not yet shared

Trinidad & Tobago listed companies, in total, have achieved the magic threshold with 30.1% female directors. However, with only 15.4% women chairs and 20% women CEOs there is still much to do. The implication is clear: board-leadership roles and executive pathways need explicit attention.

2) Law beats vibes-until culture catches up

The EU and Hong Kong show what happens when rules bite (and when they do, recruiters broaden their nets). For Trinidad & Tobago, there could be an argument for a soft-law hybrid: strengthen disclosure (e.g., require gender-diversity policies, report board and leadership gender annually), publish market-wide scorecards, and set voluntary 40% targets with clear timelines and stakeholder endorsement.

3) Refresh the slate, not just the script

Diversity stalls when boards don’t turn over, transparency and steady refreshment are essential. Consider Trinidad & Tobago-specific nudges such as term limits for independent directors, or “comply-or-explain” policies on diverse shortlists for each vacancy.

4) Intentionally build the executive pipeline

Globally, CFO/COO roles remain the feeder pool for CEOs and board leadership; the G20 numbers show the CFO gap (with only 12% women) is still wide. For listed companies, audit committee chairs and nomination committees should sponsor rotations into revenue-critical positions for high-potential women, track ready-now and ready-soon slates, and set measurable goals for women in function-critical roles (finance, operations, technology).

What “good” looks like for the next 24 months

· Targets you’ll actually hit: For boards, 40% by 2027 is credible where the starting point is ≥30%; for leadership, pick function-specific targets (e.g., CFO/COO) with annual public reporting.

· A nomination-committee charter that bites: Require diverse shortlists for every vacancy; insist on skills-based matrices (strategy, tech/cyber, climate) to avoid recycling the same profiles.

· Refreshment and tenure tools: Adopt soft term limits (e.g., 9-12 years for independent directors) and scheduled skills reviews aligned to strategy cycles.

· Data and disclosure: Even if local rules are light, publish a board and leadership diversity matrix annually (gender, and-where appropriate and lawful-other dimensions of diversity), plus progress vs targets.

· Pipeline mechanics: Put women into revenue-critical rotations, sponsor external board-readiness programs, and pair each high-potential woman with a board mentor.

Bringing it back to Trinidad & Tobago

The progress over the last seven years has been meaningful, and the sudden step-up in women chairs in 2024 shows how quickly leadership visibility can change once boards insist on it. The next leg requires building an executive pipeline and then making sure the nomination committee uses that pipeline when refresh opportunities arise. A locally tailored targets + transparency regime-learning from the UK and Singapore/HK-could deliver the gains of “hard law” without a full quota model.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Joanne G Salazar is a Caribbean Governance and Diversity Consultant